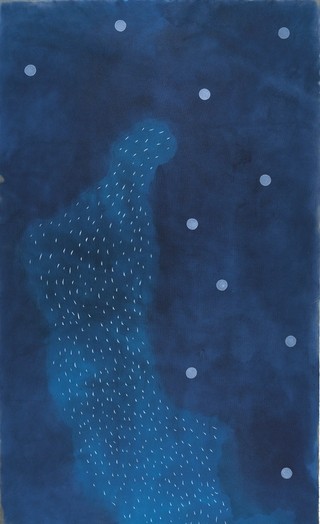

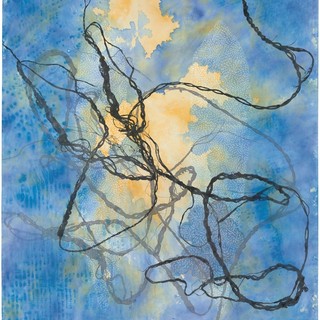

‘When I made salt in the wound in 2008/09, it was very much that shape. It is the open wound with the salt in it, which comes down through generations. A trans-generational trauma throughout history and our families.'4

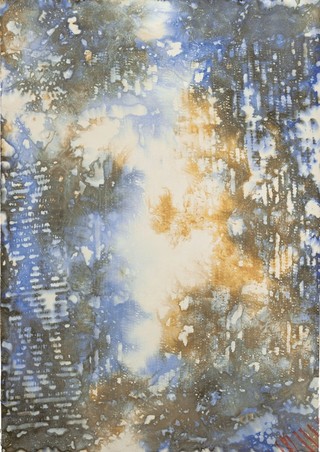

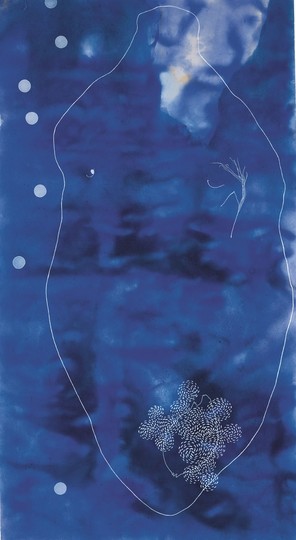

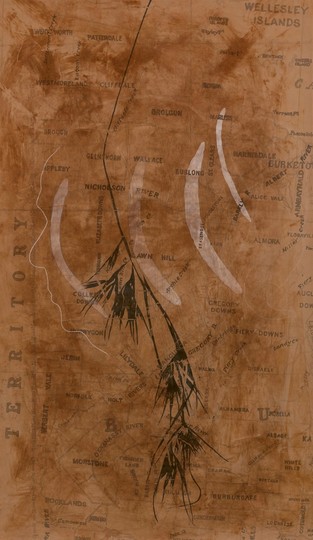

salt in the wound 2008/09 is a symbolic installation that tells a story of survival and reveals the realities of intergenerational trauma. The work honours Watson’s great-great-grandmother Rosie who hid behind a windbreak to escape a massacre by troopers. Rosie, only a young girl at the time, was bayoneted by troopers but managed to escape, along with another girl, by using rocks to submerge themselves beneath the water, using reeds to breathe through.

Watson’s installation uses leaves and branches to represent the windbreak, ochre to symbolise the shape of the wound her great-great-grandmother carried throughout her life, and salt to signify the intergenerational trauma caused by this near-fatal act. The unreconciled historic injustice perpetrated by a nation continues to reverberate through the psyche of Watson’s family.

4. Judy Watson, quoted in Paola Bella, ‘The names of places: A conversation with Judy Watson’, RMIT Gallery, viewed October 2023.