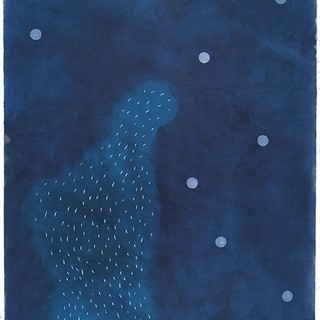

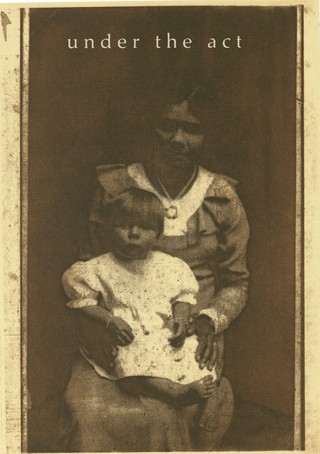

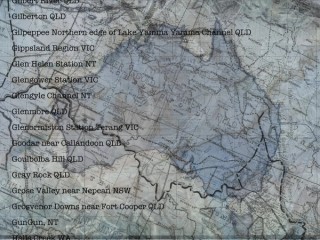

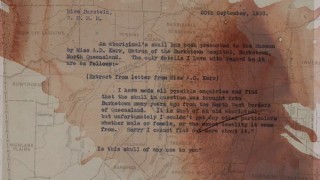

In 1995–96, Watson visited the collections of the Horniman Museum, Science Museum, and Museum of Mankind, London, and museums in Cambridge and Oxford, while researching Aboriginal collections in British museums. Her visit raised questions about how the cultural material in these museums was acquired. our bones in your collections, our hair in your collections, and our skin in your collections 1997 reference the turmoil that confronts Indigenous people when they consider ancestral human remains in museum collections.

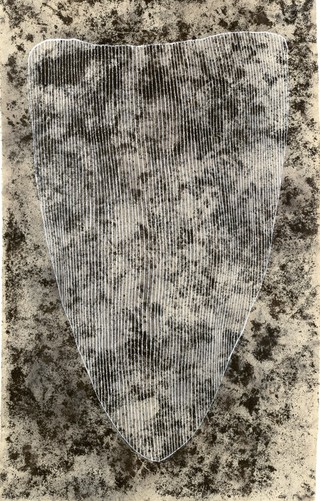

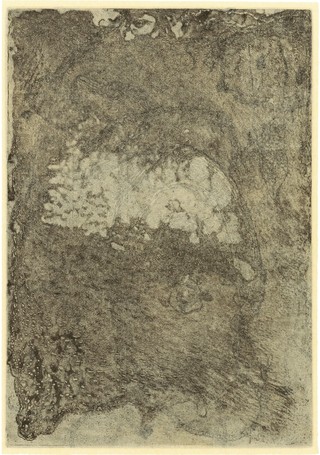

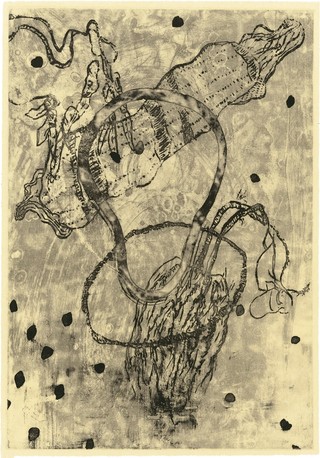

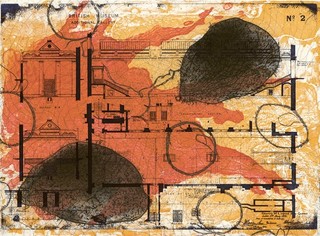

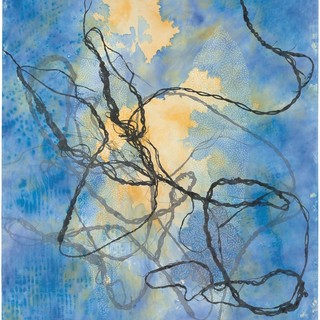

In her study of the objects in the museums, Watson wondered if those objects twined with human hair might include some of her own matrilineal ancestors’ hair. The relics that are etched in these prints come from the Gulf of Carpentaria, near Watson’s ancestral Country. They are based on her drawings of armbands, a head band, a fringed skirt, and a pituri bag used for the storing and trading of pituri (native tobacco).

The prints’ titles clearly refer to the macabre ethnocentric practice in Western anthropology of collecting and keeping human remains.